Cota 45—Rediscovering Sherry

Ramiro Ibáñez is stripping away artifice to showcase the chalky terroir of Jerez

Sherry ranks up there with Riesling and Retsina as one of the most intense and polarizing wine categories. I admit that after being intrigued by Sherry on an intellectual level I eventually was turned off by the high alcohol levels and difficulty pairing with of most of the food I ate. I knew it was a region with special terroir and history in danger of being lost to changing tastes, but my own taste was among the many that had moved away from the boozy, rich wines that had come to dominate Sherry beginning in the late 19th century with the so-called solera style.

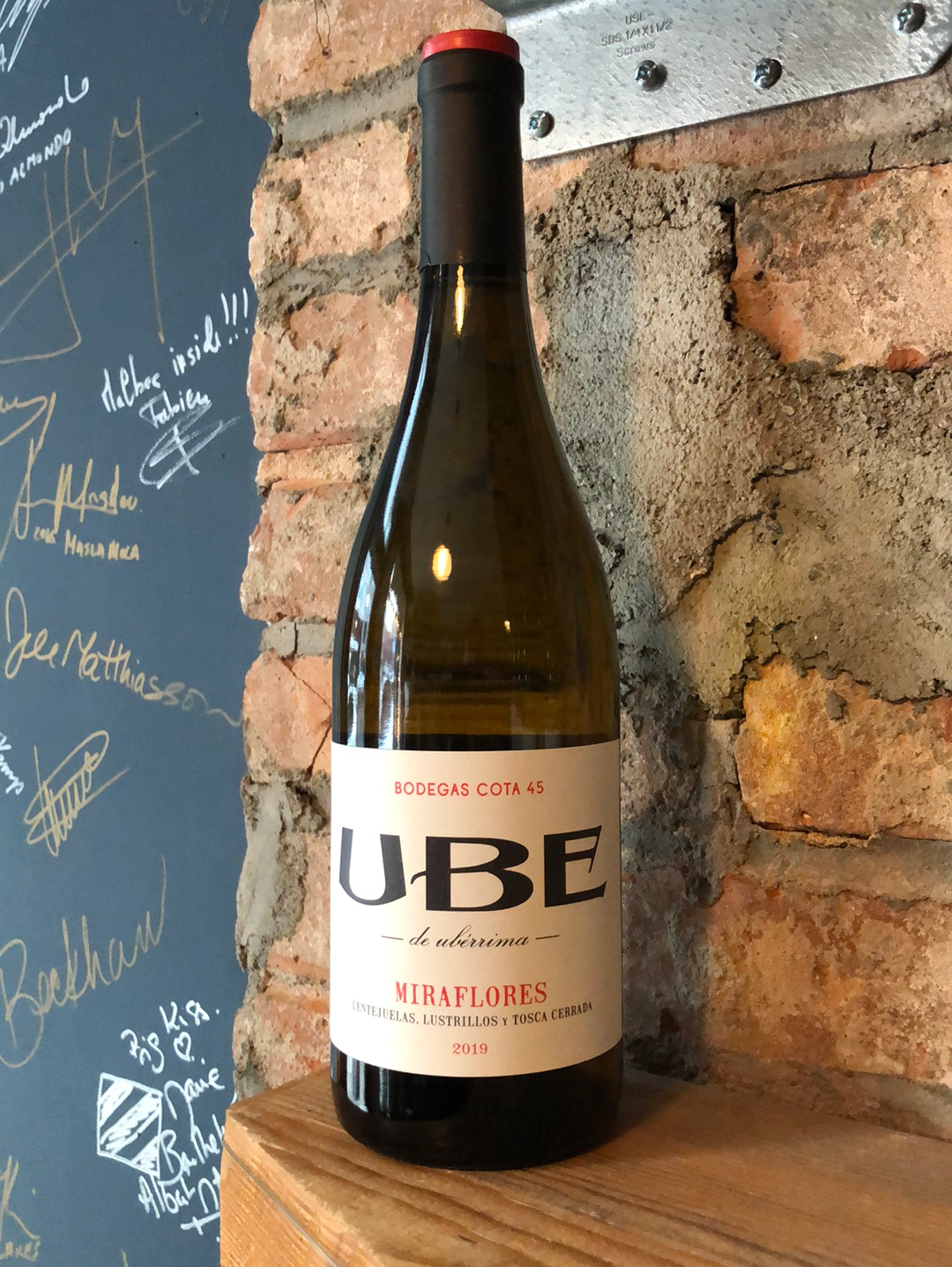

However, I have been totally rediscovering Sherry through the wines of Ramiro Ibáñez. His Cota 45 project has stripped away the artifice of the solera style and showcases unfortified wines from Sanlúcar in a way that is more akin to Burgundy. This puts the focus on albariza:the chalky soil that coats everything in Jerez from vineyards to cars to suit jackets with a fine layer of white dust. He and others are leading a growing movement that may well save Sherry. I really want to reintroduce everyone to the region, and Ramiro Ibáñez has the potential to do what Marcel Lapierre did for Beaujolais or Frank Cornelissen did for Etna.

BUY COTA 45

SHOP OUR SELECTION OF 'NEW WAVE' SHERRY

It was the British who drove demand for the opulent style of Sherry that most of us are familiar with. And while this created a huge boom in the area in the late 19th century, the dominance of the big Sherry houses also destroyed much of the local viticulture. While the rest of Europe was fueling the Golden Age of Sherry with demand for fortified Palomino Fino and Pedro Ximenez, locals in Jerez were still drinking unfortified wines. These were made from not just Palomino but over 100 other local varieties that are now nearly extinct.

Ramiro Ibáñez and a group of six other winemakers formed a group called 'Manifesto 119' that is trying to preserve many of the 119 varieties that existed in Jerez before they were nearly all ripped out in favor of Palomino. You can taste grapes like Perruno and Uva Rey in the Ramiro's resplendent Agostado 2016.

Palomino is nevertheless a beautiful grape with the transparent delicacy to express nuance between the different types of albariza and the different pagos, or vineyards, that Ramiro is passionate about. The winemaking is unadorned, and everything ferments in used manzanilla barrels. To minimize fruitiness, Ramiro used no temperature control in his cellar. The barrels are not topped-up, meaning that a layer of flor forms naturally, just as in the sous-voile wines of the Jura. Even with a light touch in the cellar these are wines with very unique flavors. But Ramiro has such an eye for detail that they are precise and graceful: words I would rarely have used for Sherry before discovering Cota 45.

The idea of showcasing terroir over technique; vineyard work over cellar work; this has brought renewed life to many wine regions from Champagne to Chianti. Ramiro is still an outlier but he is also a leader of a movement that has already caught fire. They were the spark for me; I think they'll light you up as well.

Cheers,

Jonathan Kemp

*For those interested in learning more about Sherry and the new wave of Jerez winemakers, don't miss the Feria En Rama on November 6th at the Chelsea Hotel.

|

|

|

Leave a comment